Even before its inception in 2005 I had been talking with the National Theatre of Scotland's artistic director, Vicky Featherstone, about going back to Scotland to work with the company.

It is very exciting when any theatre company is formed, especially these days, but for national government to form one is a really amazing thing. Also the NTS really benefits in not having a base building. It is a theatre without walls, and therefore it is not bound by the normal confines of where performances take place and where art can flourish.

It's opening piece Home was performed in ten different locations around Scotland including down the side of a high rise building in Glasgow. Obviously it performs in theatres of all sizes but also village halls, forests, on ferries and in airports.

Another thing that excited me was the breadth and scope of the actual work. Too often in the past Scottish theatre has been defined by its obsession with itself: a parochial approach that only rarely lights the spark that turns heads and ignites spirits. More often it merely reinforces national cliches and encourages self-absorption and jingoism.

So here is a company that is looking out to the world instead of into its own navel, challenging and inspiring, confident in itself and knowing it is only as good and will only suceed as much as it wants to. You could say it is a manifestation of Scotland itself, or the new Scotland that has emerged since it was granted devolution from the London parliament in 1997.

So, as you'll have guessed, I was very excited to work with the NTS. I had long admired both Vicky and her associate John Tiffany's work.

We toyed with a couple of ideas which didn't work either logistically or artistically and then they came to me with The Bacchae. I had never performed Greek tragedy apart from a few exercises at drama school but I have always been fascinated by it, both in how it has influenced drama through the ages, and also in how primal and basic and bawdy it is. I find that with Shakespeare too: it's easy to get florid and fancy with him but you're never far from a fart joke.

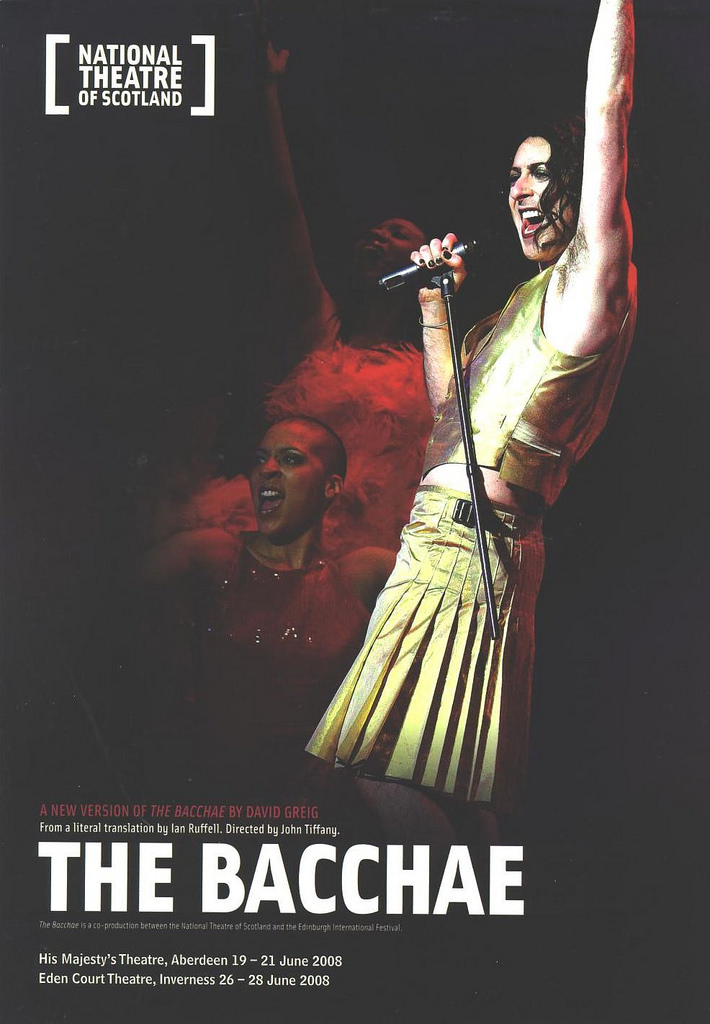

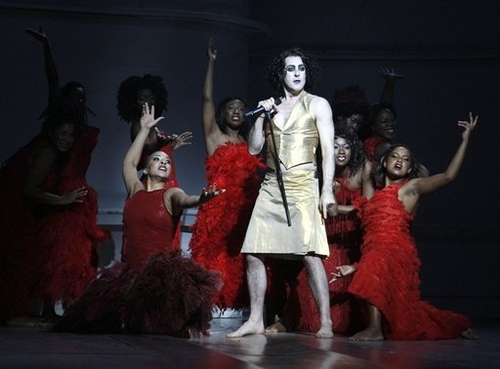

So the idea of playing the god Dionysus really appealed to me. John was directing; David Greig, an amazing Scottish playwright whose version of Casanova I had almost done in NYC with the Art Party was on board to do the adaptation. Also the production was to open the Edinburgh International Festival.

I had spent many Augusts in my youth performing at the festival, but at the much bigger and egalitarian fringe festival, never the official, posh, international festival! Victor and Barry cut their teeth there and came back to the Assembly Rooms many times. I also did a play at the Traverse in 1988, The Conquest of the South Pole which transferred to the Royal Court in London and was kind of my first big break. Also the first film I ever appeared in (Passing Glory), my first film as director (the short film Butter) and The Anniversary Party all had their UK premieres at the film festival (which used to take place at the same time as the other festivals) so I have great memories and connections.

The Bacchae turned out to be a really amazing experience, both in terms of me going back home but also in terms of the process of working with John and the cast, and feeling really excited about making something which is ostensibly perceived as ancient and with little to say today into something dynamic and contemporary.